Why is third position a minor key?

Close encounters of the third kind

Close encounters of the third kind

This question was asked by a student in our Harpin’ By The Sea beginners’ workshop; we had touched on positional playing as a way to extend the scope of the diatonic harmonica. And to be honest, it’s a fair question. Perhaps we accept the fact too easily, without asking or fully understanding the reason why. But we were a group of beginners. So we decided to explain the finer details after the workshop for those who were interested, rather than risk putting the majority off music for life. Here’s the result.

If you are unfamiliar with the concept of modes and positions, then I recommend you first check out the post entitled Modes (or visit Modes via the Theory menu at the top of the screen) and come back when you’re comfortable with everything. It’s quick and it won’t hurt!

Ground control to Major Tom

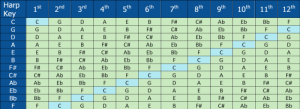

So what are positions all about? In the simplest terms, we can take a C major harmonica and use it to play in different keys just by using a different hole as our root note, or starting point, each time. Some keys will be more useful than others, but in theory we could start from any natural, sharp or flat note (black or white key on the piano) and find some fun phrases. In doing so we are inadvertently working in different musical positions. By way of example, When The Saints works well from 4B (1st position), Juke works well from 2D (2nd position), Summertime works well from 4D (3rd position)and Au Claire De La Lune is best played from 5D (12th position). To forge an answer to our original question however, we need to apply some logic and find a workable formula or DNA to explain what’s going on. Why? Because it will enable us to express ourselves as musicians rather than just harmonica players. And with this comes greater understanding and enjoyment of our instrument and music in general. The solution is where music and maths collide in the form of the circle of fifths.

So what are positions all about? In the simplest terms, we can take a C major harmonica and use it to play in different keys just by using a different hole as our root note, or starting point, each time. Some keys will be more useful than others, but in theory we could start from any natural, sharp or flat note (black or white key on the piano) and find some fun phrases. In doing so we are inadvertently working in different musical positions. By way of example, When The Saints works well from 4B (1st position), Juke works well from 2D (2nd position), Summertime works well from 4D (3rd position)and Au Claire De La Lune is best played from 5D (12th position). To forge an answer to our original question however, we need to apply some logic and find a workable formula or DNA to explain what’s going on. Why? Because it will enable us to express ourselves as musicians rather than just harmonica players. And with this comes greater understanding and enjoyment of our instrument and music in general. The solution is where music and maths collide in the form of the circle of fifths.

Thumbing a lift

Thumbing a lift

Take out your patented, circle of fifths, double-checking system; you’ll find one on the end of each arm. Starting with C on the thumb of your right hand, let’s move five steps up the musical alphabet; so, D is on your index finger, E on your middle finger, F on your ring finger and finally G on your little finger. You’ve just counted a diatonic interval of 5 degrees from C to G. Think of it as Monday to Friday if this helps. I know this is technical stuff, but you’d better get used to it. You’ve just moved from 1st position on a C harp (C), to 2nd position on a C harp (G). From your thumb to your little finger. From Monday to Friday.

Now let’s count up five degrees from G to find third position on the same C harp. Thumbs at the ready. Your thumb is now G, so your index finger becomes A, middle finger B, ring finger C and your little finger D. Getting the hang of it? You could keep this pattern going and eventually work your way round twelve different positions. Which is all well and good, but let’s just pause with third position for a moment. When we actually play along to a tune in D, we find we’re clashing badly. And that’s because our third position is actually D minor, not D major.

Beam me up Scotty

Beam me up Scotty

The majority of harp players will accept this and run with it, using third position to accompany minor chords. Fourth position does the same thing. Five up from D on a C harp is A – you can check this on your hand. The detail however, is it’s actually A minor. So how can all this be explained? When is a position major and when does it go all minor on us? Our piano keyboard will help illustrate the answer, which is intervals. The relative distance between notes.

Remember that we’re playing a diatonic instrument in C. This is the same as having a piano keyboard with no black keys. If we chose to play the C major chord using our right hand, this would not present a problem. We’d place our thumb on C (our root note), our middle finger on E and our little finger on G. That’s three notes in all, or a Major Triad. It’s a solid musical building block and it sounds complete. In scientific terms, we’re using the first, third and fifth degrees (notes) of the C major scale. But you don’t have to be scientific if you don’t want to be, just blow 1B-2B-3B together. That’s your C chord and that’s first position done. Just to reinforce things however, let’s play the C major arpeggio – or broken chord – as separate notes up and down: 1B 2B 3B 4B 3B 2B 1B

Now let’s move up to G from C for second position using the circle of fifths and follow the same process. To play the G major triad on the diatonic (white key only) keyboard, we’d place our thumb on G as the root note this time, our middle finger on B and our little finger on D. Once again we’d have a satisfying and complete sound. Try it by playing 2D-3D-4D together. And again we’ve used the first, third and fifth degrees (notes) of the G major scale. And that’s second position nailed. But again let’s reinforce things by playing the G major arpeggio up and down: 2D 3D 4D 6B 4D 3D 2D

Now let’s move up to G from C for second position using the circle of fifths and follow the same process. To play the G major triad on the diatonic (white key only) keyboard, we’d place our thumb on G as the root note this time, our middle finger on B and our little finger on D. Once again we’d have a satisfying and complete sound. Try it by playing 2D-3D-4D together. And again we’ve used the first, third and fifth degrees (notes) of the G major scale. And that’s second position nailed. But again let’s reinforce things by playing the G major arpeggio up and down: 2D 3D 4D 6B 4D 3D 2D

Take me to your leader

Are you ready for third position? We move up to D from G using the circle of fifths and place our thumb on the root note of D on our diatonic (white key only) keyboard. Our middle finger then falls on F and our little finger on A. But when we play the chord, it no longer sounds as satisfying and complete as before. It sounds forlorn. This is because it’s a minor triad. But before we explain this change in full, let’s just play the D minor arpeggio, or broken chord, up and down: 4D 5D 6D 8D 6D 5D 4D Can you hear how 5D is the ‘sad’ note? If we were to ‘cheer it up’, we’d need to sharpen or raise it a half step to make things sound major again. This would turn it  into F# rather than F. But we don’t really have an F# because we’re using a diatonic keyboard remember? White keys only. F# is most definitely a black key. So we’re kind of stuck with what we’ve got.

into F# rather than F. But we don’t really have an F# because we’re using a diatonic keyboard remember? White keys only. F# is most definitely a black key. So we’re kind of stuck with what we’ve got.

Lowering the tone

I say kind of for two good reasons. Firstly because those in the know – our advanced players – will tell you that you can find F# by overblowing hole 5. In Harp Surgery tab this would be written as 5B#. Overblowing is the technique that bends a reed pitch upwards to find a missing note – a topic we’ll cover another day. However, you’d be very hard pressed to include an overblow in hole 5 as part of a chord combination. The second reason is that by accepting third position gives us a minor key and finding pleasure in this change, we can turn a negative in to a very big positive. Just listen to Sugar Blue!

Better by half

Now here’s the bit you’ve been patiently waiting for; the underlying explanation for the change from major to minor in empirical terms. We count our intervals chromatically instead of diatonically. Cue the J.Arthur Rank gong and sweaty man. This means re-introducing the black notes of the keyboard, then recalculating the total number of half steps between the notes in our triad chords. Back to the drawing board. Starting with 1st position, or C on a C harp, we played C-E-G. Chromatically, that’s 5 half steps from C to E, and 4 half steps from E to G. Check it out on the piano above. The result of this combination of chromatic intervals is a major chord.

Now to 2nd position, or G on our C harp. Here we played G-B-D. Chromatically, that’s an interval of 5 half steps from G to B, and 4 half steps from B to D. Check it out on the piano above. Again, the result is a major chord.

Finally, let’s look at 3rd position, or D on a C harp. This time we played D-F-A. Chromatically things have now switched – that’s only 4 half steps from D to F, and now 5 half steps from B to D. Check it out on the piano above. The result of this combination of chromatic intervals is a minor chord. We’ve effectively ‘flattened’ or lowered the third degree of the diatonic scale. Which is the basic rule for turning a major key into a minor key. Or a major chord into a minor chord. And that’s all there is to it. It’s all about the half-step intervals between the notes!

G’night John Boy!

G’night John Boy!

As a post script, we mentioned 4th position above, which would be A minor on our C harp. So if we know that the A minor triad is A-C-E, let’s see if you can work out the chromatic intervals for yourself. We won’t actually find this triad chord on the diatonic harp, but the arpeggio would be 6D 7B 8B 10D 8B 7B 6D You might find use of 7B-8B as a double stop, or two-note combination, in lieu of the full chord however. Try it now and imagine you’ve just watched The Waltons.

Hello to the good Doctor !!

Greetings from Portugal for everybody

This is the best explanation I have ever read ! , just like the Modes post is clear as water

thank you and congratulations for your site , this is truly fantastic because you made everything so easy to learn this thing we all love … Harmonicas!!!

Yay! So pleased it was clear as water, rather than clear as mud. Brigado Tonio.