In a nutshell

In a nutshell

If you’re short of time, here are the essentials. A harmonica trill is normally played by sliding back and forth rapidly between two adjacent holes, either blowing, or drawing. Technically this can be achieved anywhere on the harmonica, but most often we hear it played across holes 4D~5D or 3D~4D; this produces the signature effect that everyone associates with the harmonica.

In our tab, B means blow, D means draw, and numbers indicate our target holes. The symbol ~ means trill the notes featured. And that’s all you really need to know. Here’s how it all sounds:

If you find yourself extending a trill across more than two holes or you’re holding the harmonica in one hand and using it like a toothbrush, you probably need to review your technique as the tight warbling effect will be lost. If this is close to home, stick around. We’ll look at how to trill next, then undertake some deeper analysis.

If your trills are already in check, you may like to skip the ‘how to’ tutorial that follows and move on to the more advanced sections; they may hold some details you haven’t previously considered. Whatever your skill set, it is important to play trills from a position of control. This will facilitate a consistent delivery and enable you to regulate your rate of repetition on demand. A trill is crafted, it is not a random effect.

So how do I do it?

So how do I do it?

Start by mimicking an old fashioned fire engine. Slowly draw in 5D, then slide back and forth between 5D and 4D in the same breath, ensuring your note distribution is clean and accurate. Then try an ambulance using 4D and 3D. Ideally you should have both hands on the harmonica as this will help to build muscle memory and a controlled delivery over time. Here are our first two movements played on a C harmonica.

Now reverse the delivery, entering and resolving the movement with the lower hole. Trills are generally more stable this way as we’re subconsciously providing resolution. That’s the SOS part of our title covered.

Make sure you weight each note equally, keeping the delivery symmetrical. Listen carefully to see if you are over-emphasising one side or the other. If so, slow down and establish your balance. Snatch the harp too quickly one way or the other and you create an ‘asymmetrical’ twitch rather than a balanced embellishment. If everything seems to be in check, it’s time to increase the tempo. As you do so, ensure you remain in control and don’t rush things. Remember, this is not a random effect like brushing your teeth.

Make sure you weight each note equally, keeping the delivery symmetrical. Listen carefully to see if you are over-emphasising one side or the other. If so, slow down and establish your balance. Snatch the harp too quickly one way or the other and you create an ‘asymmetrical’ twitch rather than a balanced embellishment. If everything seems to be in check, it’s time to increase the tempo. As you do so, ensure you remain in control and don’t rush things. Remember, this is not a random effect like brushing your teeth.

So it all boils down to good command of slide note technique and accurate note placement. Here’s a quick exercise to help you establish this. It’s based on the Major Scale and we’re playing in thirds by connecting neighbouring holes:

3B..4B 3D..4D 4B..5B 4D..5D 5B..6B 5D..6D 6B

6D..5D 6B..5B 5D..4D 5B..4B 4D..3D 3B..4D..4B

Now for a top tip. Work the bridge between the two target holes and make this your focus rather than the holes themselves. Play the hole divider and the trill holes will take care of themselves. This also reduces the risk of slewing too far across the target area and triggering unwanted holes. As you play the divider, the end result will be akin to a yodel or Tarzan call. As you open up and introduce tone into the equation, the result will sound rounded and satisfying on the ear.

Now for a top tip. Work the bridge between the two target holes and make this your focus rather than the holes themselves. Play the hole divider and the trill holes will take care of themselves. This also reduces the risk of slewing too far across the target area and triggering unwanted holes. As you play the divider, the end result will be akin to a yodel or Tarzan call. As you open up and introduce tone into the equation, the result will sound rounded and satisfying on the ear.

And by the way, although we’ve established that trills generally sound stronger when they start and resolve on the lower note, there are no fixed rules, so it’s perfectly acceptable to break this protocol if you deem it preferable.

What’s with the trains?

Simple. If we play our SOS trill notes together as double stops, we have the classic harmonica train sound. Add a hand wah-wah and you’re Ridin’ on the L&N.

Standard Notation

In standard notation a trill is indicated by the word trill, or its shortened term ‘tr‘, and usually accompanied by a wavy line.

Which embouchure should I use?

Trills can be achieved by puckering, tongue blocking or u-blocking; the three principal harmonica embouchures. Embouchures can be alternated for different effect too. Puckering will produce quite a bright result, while tongue blocking lends itself to a softer, darker tone. Check out the trill control and tone Little Walter uses on Blue Midnight. He’s playing Bb harp in second position.

Should I move my head or my hands?

Should I move my head or my hands?

As long as the result is controlled and pleasant on the ear, who cares? How a trill is achieved is completely subjective. Some players will no doubt use a hybrid of hands and head. Others may adopt entirely separate systems, which we’ll touch on later. Either way, descent into tribal debate is fruitless. Nevertheless, if you’d like a brief and objective diversion into this topic, check out our exposé here. Now for some terminology.

Hand Roll

The lateral movement necessary to achieve a trill is sometimes referred to as a roll or shake. Moving the harp laterally as you play is a hand roll, or hand shake. Perhaps it should also be called a ham roll. The embouchure used in conjunction with this method doesn’t really matter.

Head Roll

A trill can also be achieved by rolling or shaking the head from side to side. This is a head roll, or shake. It looks great on stage, but avoid applying it too vigorously. This could conceivably cause injury and may affect the quality of the trill. Once again, the embouchure used in conjunction with this method doesn’t really matter.

Tongue Roll

Tongue Roll

This is a less conventional technique, but no less valid. It can be used to trill adjacent holes and holes a greater interval apart. The technique is achieved by placing the tongue onto the harmonica mouthpiece, framing the required interval with the mouth, then shuttling the tongue from side to side to activate the trill. It’s different to a tongue sweep, however. A tongue sweep delivers a broader sound effect, with a sound more akin to the strum of a Spanish guitar. In the examples below, we hear a couple of trills played on adjacent holes, then on holes an interval apart, and finally some tongue sweeps.

Mick Kinsella has tongue roll tracks in his excellent beginner’s blues module – Blues Harp From Scratch (ISBN 0-7119-4706-6). In Mick’s words, ‘although the effect is the same as the head roll, the tone is quite different. The tongue roll is easier than the head roll when playing fast tunes.’ Practise makes perfect.

(ISBN 0-7119-4706-6). In Mick’s words, ‘although the effect is the same as the head roll, the tone is quite different. The tongue roll is easier than the head roll when playing fast tunes.’ Practise makes perfect.

Jaw Swing

Jaw Swing

It is also possible to execute a trill by swinging the jaw, although this can feel awkward to the uninitiated. Made famous by Charlie McCoy, the jaw swing is used to navigate complex country harmonica sequences at speed. In situ, the technique can be used to alternate between adjacent holes, thereby creating a trill. In his own live performances however, Charlie appears to cup the vocal mic and roll the harp with his hands when a trill is required.

How fast or slow should I play my trill?

Like good vibrato, you can alter the rate of a trill in sympathy with the tempo and mood of a piece of music. A rapid trill over a slow blues, for example, may be less effective than a more gently paced trill. Equally a slow trill over fast sequence will drag. Judge it and remember the song is always king.

Of course a trill needn’t be played at one tempo either. Controlled mastery of the technique will enable the player to enter slowly, speed up and exit at will, fast or slow. This creates added texture and interest.

Walking the trills

Another popular aspect of trilling could be called walking the trills. One great example is Easy, played by Big Walter Horton on a Bb harmonica.

Another popular aspect of trilling could be called walking the trills. One great example is Easy, played by Big Walter Horton on a Bb harmonica.

3D~4D 4B~5B 4D~5D 4D~5D 5B~6B 4D~5D 4B~5B 3D~4D

5B~6B 5D~6D 5B~6B 5B~6B 5B~6B 5D~6D 5B~6B 4D~5D

The underlined notes plot the underlying melodic thread. For authenticity, note that Walter doesn’t active 7B as this is not part of the melody. Consequently the trilled combinations juggle the melody line between the lower and upper note as you play through the sequence.

Another exponent of travelling trills is Mark Feltham of Nine Below Zero. In the following clip we can hear him on Pack Fair & Square using an F harmonica:

3D~4D 5B~6B 5D~6D 5B~6B 4D~5D 4B~5B 3D~4D

3D~4D 5B~6B 5D~6D 5B~6B 4D~5D 4B~5B 3D~4D

And at the close of Ridin’ On The L&N using a D harp. Note how his use of portamento as he enters the trilled passages.

4D~5D…….5D~6D…….

How should I practise my trills?

Select a particular trill. Start the trill evenly and slowly. Pick up the tempo but maintain control at all times. Be meticulous. Take the trill up to top speed, hold it there for a moment and then slow right down again, emulating the decay of a basketball dropped from height. This should be achieved in one breath and will deliver a sense of accomplishment.

Which holes should I trill?

Which holes should I trill?

The classic trill is 4D~5D, followed by 3D~4D. On one version of ‘Walter’s Boogie’, Walter Horton extends down to a trill across blow holes 1B~2B. On other blues tracks players trill across blow holes 8B~9B at the top end of the harp. In third position the blow and draw trills in 5B~6B and 5D~6D are very effective. Listen to songs and notice which trills are used and when. Some lend themselves to the main chord. Others lend themselves to other stations in a chord progression.

When should I trill?

Be judicious. Listen to examples in recordings. Try not to over-use trills or rely on them too much as a beginner. Trills can work well as a quiet backdrop to a vocal section, or across a quiet instrumental section. They also work well as the climax to a solo, the close of a song, or as a barnstorming entrance to a piece. And remember a trill needn’t be protracted. Little Walter frequently decorated phrases with a touch of the 3D~4D trill.

9 Below Zero’s take of Rocket 88 shows that a trill can be used as much or as little as you like across the right chords. Check out the clip at the foot of this page. In the wrong hands a trill can quickly become overused, whereupon it becomes predictable and meaningless. Better to judge things musically, trilling over the optimum spots in a piece or a phrase. Mick Kinsella’s Southern Jive takes you round the chords beautifully, with optimum use of trills. We really recommend his Blues Harp From Scratch

9 Below Zero’s take of Rocket 88 shows that a trill can be used as much or as little as you like across the right chords. Check out the clip at the foot of this page. In the wrong hands a trill can quickly become overused, whereupon it becomes predictable and meaningless. Better to judge things musically, trilling over the optimum spots in a piece or a phrase. Mick Kinsella’s Southern Jive takes you round the chords beautifully, with optimum use of trills. We really recommend his Blues Harp From Scratch book for beginners as it promotes best musical practice and avoids over-reliance on comfort zones.

book for beginners as it promotes best musical practice and avoids over-reliance on comfort zones.

How else can a craft my trills?

As well as verifying the tempo of a trill delivery, why not introduce dynamics too? Start slowly and quietly, pick up speed adding a crescendo as you do so, then diminuendo and return to a slower delivery. Pour some emotion into the delivery too and your audience will be very satisfied. Here’s a reproduction of the 5B~6B to 5D~6D trill from Steve Baker’s Double Crossed & Blue in 3rd position, demonstrating use of dynamics.

Can I use bending skills when trilling?

Can I use bending skills when trilling?

Absolutely, and in various ways. Portamento is the ability to bend into a trill. A typical example is to enter a 4D~5D trill from the bent 4D’ hole. This gives real character to the whole effect. Visit our Glissando and Portamento page for further information on this technique. Here it is on a C harmonica

You can also bend a trill itself. It’s something you can hear in numerous harp tracks. Typical examples are 3D~4D, 4D~5D, 8B~9B. Here they are on an G harmonica.

Can you trill a blow and draw note pair?

Yes, but it’s unusual. Using your diaphragm or cheeks, you can pass air rapidly between the blow and draw note in the same hole, which is technically speaking a trill. 5B~5D and 7D~ 7B will deliver semitone interval like the examples at the start of this study, while three, four and five half step intervals are achievable in other holes. Here are the 5B~5D and 7D~7B trills, each played from the diaphragm first and then from the cheeks:

Trying this in adjacent holes is also possible, however it tends to impair the rate of movement and accuracy necessary for an effective trill. Other aspects of trilling technique are also compromised, such as portamento.

Can you trill with one hand?

Can you trill with one hand?

Yes, but you will arguably have less control if you are moving the harmonica rather than your head. You can easily end up with a frenzied ‘toothbrush’ effect. Two hands provide the push-me-pull-you tension for controlled shuttling of the harmonica. If you prefer to use a head role, then two hands will provide greater support of the harmonica as you deliver your trill too. One hybrid solution we have encountered is where the harmonica is held in one hand to provide the trill movement, while the palm of the free hand is held vertically as a buffer for the extended end of the harmonica to abut.

Digging deeper

We have a good idea what a harmonica trill sounds like from the clips above. For comparison with other instruments however, let’s check the following clip. Here we have trills played on a piano, a flute and a clarinet respectively. The piano is trilling Db and D, the flute is trilling G and Ab, and the clarinet is trilling F and F#. Note how each example is balanced and consistent. Note also how last of example, the clarinet, slows down as it closes. This demonstrates how the player has full control of their decorative delivery.

It is worth noting that the examples use target notes a semi-tone apart. The notes are essentially dissonant, which generates an air of tension. This is a standard chromatic trill, which passes between the target note and its neighbouring auxiliary note one half step above. The alternative is a diatonic trill, where the auxiliary note is one step up the scale being used. In this case the auxiliary note would usually be a whole step above the target note, though not always.

By contrast, trilling between adjacent holes on a standard tuned diatonic harmonica will deliver a minimum interval of three half steps (6D~7D), but more normally four, five and even six half steps. Arguably the result is more stable. So, the provision of trills can also be dependent on the instrument used. In which case we could claim that a trill can harness any two notes, regardless of their proximity.

Nevertheless, the essence of an effective trill is controlled movement between the target notes. Here is a 1D~2D trill (a six half-step interval) and a 6D~7D trill (a three half-step interval) played on a C harmonica.

On a final thought regarding trill note proximity, while a pianist’s span could trill two notes an octave or more apart, a harmonica player’s options are more limited in this context. Through interval playing (a form of tongue blocking), it is perfectly possible to activate and trill pairs of notes an octave apart on the harmonica. We can hear this in the example below, first trills hole 1D=4D~2D=5D, then 4D=8D~5D=9D. The symbol = denotes octaved pairs.

However, it’s far harder to trill two individual notes that are not in the same or adjacent holes. This requires highly accurate tongue switching technique, whereby the chosen targets are played from opposite corners of the mouth as the tongue shuttles laterally. Here is a tongue trill played on holes 2D~4D on a C harmonica, missing out 3D.

Trill Scrap Book

To close, here is a short collection of notable trills. See if you can work out the song key, harmonica position and holes being used.

Little Walter – Mean Old World

Walking To My Baby – The Fabulous Thunderbirds

Rocket 88 – Nine Below Zero

Flat Foot Sam bought an automobile

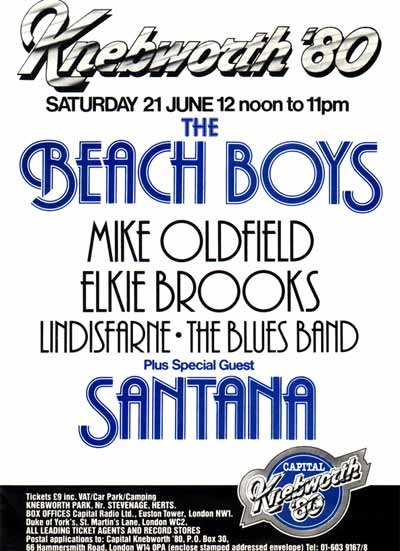

Flat Foot Sam bought an automobile A year later, amidst great media interest, The Blues Band took the stage at the 1980 Knebworth Festival. The Good Doctor was in the crowd with the ‘naughty botty’ gang, ready for a musical feast which also featured Lindisfarne, Elkie Brooks, Santana and The Beach Boys. It was a fabulous day compered by Richard Digence and the bands were exceptional. After the festival, one song in particular stuck in the Doctor’s mental jukebox – Flatfoot Sam by The Blues Band. It was his favourite track on their Bootleg LP and just as good performed live.

A year later, amidst great media interest, The Blues Band took the stage at the 1980 Knebworth Festival. The Good Doctor was in the crowd with the ‘naughty botty’ gang, ready for a musical feast which also featured Lindisfarne, Elkie Brooks, Santana and The Beach Boys. It was a fabulous day compered by Richard Digence and the bands were exceptional. After the festival, one song in particular stuck in the Doctor’s mental jukebox – Flatfoot Sam by The Blues Band. It was his favourite track on their Bootleg LP and just as good performed live.

In a

In a

So how do I do it?

So how do I do it? Make sure you weight each note equally, keeping the delivery symmetrical. Listen carefully to see if you are over-emphasising one side or the other. If so, slow down and establish your balance. Snatch the harp too quickly one way or the other and you create an ‘asymmetrical’ twitch rather than a balanced embellishment. If everything seems to be in check, it’s time to increase the tempo. As you do so, ensure you remain in control and don’t rush things. Remember, this is not a random effect like brushing your teeth.

Make sure you weight each note equally, keeping the delivery symmetrical. Listen carefully to see if you are over-emphasising one side or the other. If so, slow down and establish your balance. Snatch the harp too quickly one way or the other and you create an ‘asymmetrical’ twitch rather than a balanced embellishment. If everything seems to be in check, it’s time to increase the tempo. As you do so, ensure you remain in control and don’t rush things. Remember, this is not a random effect like brushing your teeth. Now for a top tip. Work the bridge between the two target holes and make this your focus rather than the holes themselves. Play the hole divider and the trill holes will take care of themselves. This also reduces the risk of slewing too far across the target area and triggering unwanted holes. As you play the divider, the end result will be akin to a yodel or Tarzan call. As you open up and introduce tone into the equation, the result will sound rounded and satisfying on the ear.

Now for a top tip. Work the bridge between the two target holes and make this your focus rather than the holes themselves. Play the hole divider and the trill holes will take care of themselves. This also reduces the risk of slewing too far across the target area and triggering unwanted holes. As you play the divider, the end result will be akin to a yodel or Tarzan call. As you open up and introduce tone into the equation, the result will sound rounded and satisfying on the ear.

Should I move my head or my hands?

Should I move my head or my hands? Tongue Roll

Tongue Roll Jaw Swing

Jaw Swing

3D~4D 5B~6B 5D~6D 5B~6B 4D~5D 4B~5B 3D~4D

3D~4D 5B~6B 5D~6D 5B~6B 4D~5D 4B~5B 3D~4D  Which holes should I trill?

Which holes should I trill? 9 Below Zero’s take of Rocket 88 shows that a trill can be used as much or as little as you like across the right chords. Check out the clip at the foot of this page. In the wrong hands a trill can quickly become overused, whereupon it becomes predictable and meaningless. Better to judge things musically, trilling over the optimum spots in a piece or a phrase. Mick Kinsella’s Southern Jive takes you round the chords beautifully, with optimum use of trills. We really recommend his

9 Below Zero’s take of Rocket 88 shows that a trill can be used as much or as little as you like across the right chords. Check out the clip at the foot of this page. In the wrong hands a trill can quickly become overused, whereupon it becomes predictable and meaningless. Better to judge things musically, trilling over the optimum spots in a piece or a phrase. Mick Kinsella’s Southern Jive takes you round the chords beautifully, with optimum use of trills. We really recommend his  Can I use bending skills when trilling?

Can I use bending skills when trilling? Can you trill with one hand?

Can you trill with one hand?