Modes

..The Dormouse had closed its eyes by this time, and was going off into a doze; but, on being pinched by the Hatter, it woke up again with a little shriek, and went on: “—that begins with an M.. (Alice In Wonderland – Lewis Carroll)

..The Dormouse had closed its eyes by this time, and was going off into a doze; but, on being pinched by the Hatter, it woke up again with a little shriek, and went on: “—that begins with an M.. (Alice In Wonderland – Lewis Carroll)

Why is it the slightest hint of the M word triggers narcolepsy in harmonica players? We smile wistfully, we nod politely, then we glaze over and let everything entering one ear pass straight out of the other. In fact the quicker, the better – we’ve enough trouble in our day already. Basically, talk of modes never, ever, makes sense and a visit to the dentist for a double root canal filling would be infinitely more pleasurable. Aren’t modes what jazzers do? We play blues, and blues comes from the heart right? Well, listen up and listen good – WRONG! Here’s how it all works..

From a position of musical knowledge, modes enable us to build on what we’re already doing. Avoiding some of the more obvious musical bear traps, we can learn to deliver measured and original musical contributions instead of peddling our shabby line of harmonica guesswork. So if your playing has lost its mojo, messing around with modes and positional playing is probably the tonic you need.

Diatonic Scale

Imagine we had a piano with no black keys so it offered only the white keys of the C major scale. This would be a diatonic keyboard. It would give us the notes C D E F G A B and C again. That’s an eight note sequence, or octave. It’s what’s in our C harp between the holes of 4 and 7 : 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B. These are our melody or soloing notes.

Imagine we had a piano with no black keys so it offered only the white keys of the C major scale. This would be a diatonic keyboard. It would give us the notes C D E F G A B and C again. That’s an eight note sequence, or octave. It’s what’s in our C harp between the holes of 4 and 7 : 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B. These are our melody or soloing notes.

Chromatic Scale

If we then added the black notes to the piano, it would become a chromatic keyboard, enabling us to ascend or descend in half note steps. If we did this between two C keys, the result would be:

Ascending : C C# D D# E F F# G G# A A# B C

Descending : C B Bb A Ab G Gb F E Eb D Db C

That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes C# is the same note as Db on a chromatic keyboard. This aspect of musical theory is called enharmonics; two names for the same note. Knowing exactly how, and exactly when to use each, is theory for another day. On diatonic harmonicas, and on a bandstand however, you’ll normally hear the notes of the chromatic scale referred to as follows:

That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes C# is the same note as Db on a chromatic keyboard. This aspect of musical theory is called enharmonics; two names for the same note. Knowing exactly how, and exactly when to use each, is theory for another day. On diatonic harmonicas, and on a bandstand however, you’ll normally hear the notes of the chromatic scale referred to as follows:

Common use : C Db D Eb E F F# G Ab A Bb B C

How to crack the modal code

Using only the white keys of the C major scale, we could experiment ascending and descending between any two like notes an octave apart; D to D, or E to E for example. If we follow this in sequence, starting with C, the result would be the chart below. Play these lines up and down a few times and notice the change of character each one takes.

C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B

C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B

D 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D

E 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B

F 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D

G 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D 9B

A 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D 9B 10D

B 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D 9B 10D 10B

Now let’s analyse what’s happening by mapping out the musical steps we’re taking in each line. Referring to the piano keyboard will help us to picture what’s going on. We’ll call a whole tone step T and a half tone (or semi-tone) step s.

C T T s T T T s C D E F G A B C

D T s T T T s T D E F G A B C D

E s T T T s T T E F G A B C D E

F T T T s T T s F G A B C D E F

G T T s T T s T G A B C D E F G

A T s T T s T T A B C D E F G A

B s T T s T T T B C D E F G A B

And this is almost all we need to know. Can you see how the semi-tone (half) steps shift to the left (down) each time we move up a note? This is what changes the ‘flavour‘ of each sequence you played  above. The semi-tones are moving closer to the start note each time, until they even become the start note.

above. The semi-tones are moving closer to the start note each time, until they even become the start note.

Name and shame

We’ve used the term ‘flavour‘ advisedly. We could have used ‘mood‘ but we don’t want to confuse this with mode, so we’ll stick with the cooking metaphor for now. In which case, just as we give each tone a name of the alphabet so that everyone understands which ingredient we’re using, so each of the diatonic dishes above, or modal scales, is given a name:

C T T s T T T s Ionian

D T s T T T s T Dorian

E s T T T s T T Phrygian

F T T T s T T s Lydian

G T T s T T s T Mixolydian

A T s T T s T T Aeolian

B s T T s T T T Locrian

These are ancient Greek terms. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was so highly regarded, they actually included it in the ancient Olympic Games. The Dorians were one of the four major Greek tribes that came from central Greece – they built temples with plane looking, or Doric, columns. Locrians were a minor tribe from north-west mainland Greece. Two of the other major Greek tribes were the Ionians who settled the Ionian seaboard in what is now Turkey, and the Aeolians, originally from Thessaly in mainland Greece. The Phrygian community was from Asia Minor (Turkey), as were the Lydians of Anatolia. Myxolydian means half, or almost, Lydian, and is a technical afterthought rather than a tribe of short stature

These are ancient Greek terms. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was so highly regarded, they actually included it in the ancient Olympic Games. The Dorians were one of the four major Greek tribes that came from central Greece – they built temples with plane looking, or Doric, columns. Locrians were a minor tribe from north-west mainland Greece. Two of the other major Greek tribes were the Ionians who settled the Ionian seaboard in what is now Turkey, and the Aeolians, originally from Thessaly in mainland Greece. The Phrygian community was from Asia Minor (Turkey), as were the Lydians of Anatolia. Myxolydian means half, or almost, Lydian, and is a technical afterthought rather than a tribe of short stature

Philosophically Speaking

Relating each of the modal scales to parts of the known world made the ‘flavour‘ of the mode more meaningful to the listener. Today we might call Phrygian the Spanish or Moorish mode, Mixolydian the Scottish mode, Aeolian the Klezmer or Yiddish mode and Dorian the English Folk mode. Meanwhile, philosophers might describe the ‘feeling‘ or ‘mood-changing‘ effect of each mode in the following ways:

Ionian Harmonious or tender

Dorian Serious or melancholic

Phrygian Mystic

Lydian Happy or vibrant

Mixolydian Angelic or youthful

Aeolian Sad or tearful

Locrian Wistful or yearning

Getting real with it

Now that the underlying theory is clearer, one important question arises; what practical use is there for musical modes when playing the diatonic harmonica? The answer in one word is, lots! But first we have to translate everything into harmonica speak.

So to start with, it’s useful to equate each mode name to a standard key name, pick a useful root note (or start point for each key), and add a memorable tune as a blueprint for recalling the mode in a practical sense. Using a C major harmonica, our shortlist might look like this:

Mode Key Root Note(s) Memorable tune

Ionian C major 4B When The Saints Go Marching In

Dorian D minor 4D Scarborough Fair

Phrygian E minor 5B, 2B Knights in White Satin (Moody Blues)

Lydian F major 5D Au Claire de la Lune

Mixolydian G major 2D, 6B Norwegian Wood (Beatles)

Aeolian A minor 6D When Johnny Comes Marching Home

Locrian B diminished 3D, 7D She’s A Rainbow (Rolling Stones)

Running around in circles

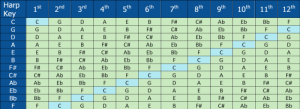

To relate the concept of modes as close as possible to every-day, 10 hole diatonic harmonica playing, we have to embrace the next area of theory. It’s another one that causes eyes to glaze over; the circle of fifths (or positional playing). Relax – it’s really quite simple. And while we won’t go into anything in depth on this particular page, let’s gently set the ball rolling using a C harp.

We know we can play any number of straight harp tunes, including When The Saints Go Marching In, from 4B right? We also know this is called 1st Position. But to put it politely, these tunes can soon become pedestrian. We want to rock it up! So we turn to 2D as our root and range up and down between 2D and 6B. We then start to investigate draw bends.  As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing cross harp in G. We also know this as 2nd Position. But let’s revisit what just happened for moment. To reach G from C, we’ve gone up 5 degrees, or major scale notes. If we want to use posh musical vocabulary, we can also call this a diatonic interval of 5. We’ve gone from C, through D E F and up to G in 5 steps. Remember that we include the root note of C as step 1 when we start counting. It’s like the working week from Monday to Friday – five days in all.

As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing cross harp in G. We also know this as 2nd Position. But let’s revisit what just happened for moment. To reach G from C, we’ve gone up 5 degrees, or major scale notes. If we want to use posh musical vocabulary, we can also call this a diatonic interval of 5. We’ve gone from C, through D E F and up to G in 5 steps. Remember that we include the root note of C as step 1 when we start counting. It’s like the working week from Monday to Friday – five days in all.

Stepping back into modal terms for a moment (and yes, you can do this), we’ve moved from Ionian (C) out of root note 4B, to Mixolydian (G) out of root note 2D. It’s that simple.

Stepping back into modal terms for a moment (and yes, you can do this), we’ve moved from Ionian (C) out of root note 4B, to Mixolydian (G) out of root note 2D. It’s that simple.

If we counted up another interval of 5 from G, we’d reach D and that would be Dorian mode. Hold up the fingers and thumb of either hand and double-check this: G A B C D. You just used your naturally patented, circle-of fifths, double-checking system. Take it with you whenever you play. By the way, to be absolutely accurate, we actually found D minor, but we’ll tackle the reasons behind this another time.

Position-wise, we can keep going round the circle of fifths until we return to C. In doing so, we will have covered all twelve degrees of the chromatic scale. I hear you asking how come, when 5 up from F brings us back to C? Fingers and thumb at the ready. Counting round in diatonic intervals steps of 5 would take us from C to G, G to D, D to A, A to E, E to B, B to F and finally from F to C. So you’re quite right.

But to be scientifically accurate, we need to count not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps. This way the chromatic interval between C and G is 8 degrees or half steps. You’ll need both hands for counting now, but keep your socks on. The keyboard image above should help to illustrate this too. The chromatic interval from G to D is also 8 degrees or half steps. If we continued counting this way, we’d eventually cover all 12 degrees of the chromatic scale:

But to be scientifically accurate, we need to count not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps. This way the chromatic interval between C and G is 8 degrees or half steps. You’ll need both hands for counting now, but keep your socks on. The keyboard image above should help to illustrate this too. The chromatic interval from G to D is also 8 degrees or half steps. If we continued counting this way, we’d eventually cover all 12 degrees of the chromatic scale:

C G D A E B F# Db Ab Eb Bb F

This is the blueprint for all twelve positions on a C major diatonic harmonica. You can take this same 8 half-step formula and apply it to any major harmonica key to work out its corresponding twelve positional names. At the same time, you can confidently accept that you’ll coincide with the seven modes as you go (in bold above). The modal positions also happen to be the most practical of the twelve options available to diatonic harp players – 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th and 12th – as the root note is not always hidden in an inconvenient bend. Just to round things off, here are the 7 modes again with their root notes and corresponding position on the harmonica, again using a C major harp.

Mode Key Root Note(s) Harp Position

Ionian C major 4B 1st position

Dorian D minor 4D 3rd position

Phrygian E minor 5B, 2B 5th position

Lydian F major 5D 12th position

Mixolydian G major 2D, 6B 2nd position

Aeolian A minor 6D 4th position

Locrian B diminished 3D, 7D 6th position

If any of this is page unclear, it’s probably because you’re human, or else you’ve been playing your harmonica instinctively. The message is, it’s time to start playing smart as well as hard, so review the information above and add it to your arsenal. We guarantee it will help shape you into a musician. Very soon you’ll be surprising those who assumed you were ‘just another harp player’.

If any of this is page unclear, it’s probably because you’re human, or else you’ve been playing your harmonica instinctively. The message is, it’s time to start playing smart as well as hard, so review the information above and add it to your arsenal. We guarantee it will help shape you into a musician. Very soon you’ll be surprising those who assumed you were ‘just another harp player’.

Interesting! Been playing blues harp, in 2nd position for around half a century, then listened to Terry McMillan on Larry Carlton’s Renegade Gentleman, and couldn’t play it. Now I know why.

so instead of playing different harps play modes on one harp. ie c harp 1 c maj 2 dmin 3 emin 4 f maj 5g maj 6 min 7 min or half dim u can do this on one harp.

Hi Tommy, that doesn’t sound quite right. On a C harp..

1st position C maj (root 4B) Ionian Mode

2nd position G maj (root 2D) Mixolydian Mode

3rd position D min (root 4D) Dorian Mode

4th position A min (root 6D, or 3D”) Aeolian Mode

5th position E min (root 5B, or 2B) Phrygian Mode

6th position B min (root 3D, or 7D) Locrian Mode

12th position F major (root 5D) Lydian Mode

ok but the point is playing 7 modes on one harp maj min min maj maj min min.

.

Hi Tommy. The answer might be yes, but at the risk of being pedantic, it depends where you’re starting your list from? I can see the right number of major and minors, but they don’t seem to be in any particular order. My apologies if I’m missing the point. The answer is certainly yes if we’re simply quantifying what’s available.

c f Bb Eb Ab Db Gb . harp keys playing in the key of c concert.

Really helpful article, finally I can start transposing my music with purpose! Would the root note of 7B also function as E minor/5th position along with 2B and 5B?

Pardon, I meant to ask if playing from the root note 8B would be in the key of E minor?

Thanks Jackeline. Yes 8B! Phrygian mode.

I can’t see the point of bothering with major and minor terms, when using them alongside the names of the modes. For me the names of the modes (i.e. the names of the step patterns) cover it. There are only seven patterns to remember, and they ain’t gonna change!

It helps when trying to understand the character of each mode, but if you’re ok without digging this deep that’s perfectly reasonable Pete.